I am worried about a break with Europe and not reassured by any of the politicians who say “it’s the will of the people” or even those who say “they’ll come to their senses.” One of the claims was that a small majority of voters didn’t want “them” coming over here to take our jobs and housing. Even the poorly-paid jobs and the oligarch’s over-priced mansions. So if the concern is invalid, would realising it make a difference in another vote about accepting or rejecting whatever deal is stitched up to guide the impact of austerity on an isolated UK?

I read “Labour mobility in the European Union: a brief history” a summary by Jonathan Portes on the website of National Institute of Economic and Social Research. This has many positive things to say about true economic impact of the mobility of workers across Europe. He summarises the research which shows that worker mobility across Europe isn’t the threat that fuelled the vote against remaining in Europe. (This is part of a longer article which details all the research sources, so, if you need them, they are at this link. )

The summary is worth reading as it has a response from Dr Niall Caldwell, with a critique of the conclusions and the modelling used in the original article. Niall feels that there is insufficient recognition of the forces which spring or oscillate in the model of dynamic interactions of demand and supply of labour in different countries. I didn’t warm to his counter-argument. Part of Dr. Caldwell’s reply identifies the force of popular opinion as a potent trigger in political outcomes. People had local perceptions which drive their view, irrespective of economic analysis. So, even if the facts are as stated in the original article, it won’t convince the voters or their politicians? I was reminded of Sorel’s views of the reality of myths, which I really must not re-read, as I have work to do.

I imagine popular sentiment, as a driver for political decisions, is a self-reinforcing whirlwind, becoming untameable with every repetition of “it’s the People’s Will.” Yet popular sentiment can be fierce when it senses disappointment and it can and does change.

There are two possible scene-changers in this perceived popular opinion, where reality may collide with perception and have an actual impact.

Firstly I was struck by Dr. Caldwell’s point that, “Immigrants do not bring their social housing, health, education and transport services with them.” I think any analysis will demonstrate that many immigrants provide a net contribution to national health services and house building. Predominantly they bring with them their own training, skills and education, which largely have been paid for in and by their country of origin, representing a brain drain in our direction. They pay proportionately from their work and from their current tax contributions for their and for their families’ use of current UK services. But some benefits provided currently are thought of as being funded from historic contributions*. What if some current costs were to be charged against contributions made historically in those countries of origins? For example, services in old age? A political solution to correcting any imbalance of service use could include the sort of recharging which is already available for health services, but seemingly underused by UK. So that some services are recharged by the host country against contribution records of whichever country took those contributions and presumably retain them. This, to put it the other way round, may mean that UK taxes pay for the care needs of elderly UK retirees to France, Spain, etc. -after all they made UK NI contributions during their working lives towards care in later lives. The same provision could made for example for Romanian tax contributions to pay towards the hypothetical elderly Romanian in Rochdale. The balance in that instance would probably be a disadvantage to UK. But that reality of a proper system and the recognition of what it costs the UK would break the myth more than the mere facts would.

The second scene-changer is for a demand for the end to mobility of capital alongside the end to labour mobility. If jobs move out of U.K. with no concomitant rights for workers to follow their jobs, there would be an imbalance, rightly resented. As someone who works in Europe occasionally, I can see this as a worry to many, as a hard Brexit makes some moves of Europe-focussed jobs inevitable out of UK.

I am watching closely the increase of poverty and austerity measures which is gnawing at the public perception that we are a successful nation as we fail to manage public transport, health, social care, amenities and on a more personal note, fail to manage publicly owned woodlands and national parks. After continuing devaluation and inflation spiralling upwards as UK wages try to catch up with costs of imported services, the drive to find work outside UK starts to be a significant attraction. Which will hurt when denied by a end to mobility. Add that to the imbalance of an outflow which already goes off-shore of wealth, potential tax revenues, investment capital and ownership of public assets, the next public outcry could well be to “Bring back our financial sovereignty,” or “Bring back our wealth,” or to end the mobility of capital.

The Trump “xx nation-first” policy has a resonance across the new radical right parties of Europe, with the prospect of more protectionism and an intended restriction of goods and services to autochthonous ones, then all the four planks of European mobility policies are imperilled. Even without barriers to the trading of good and services, the concern about the overseas outflow of wealth, tax liabilities and investment looks like a future hobby-horse for the demagogues of right and left.

But the Brexit-advocating media, who rode the public demand for ending European workers’ mobility into UK, will find unpalatable any call for the end to mobility of capital.

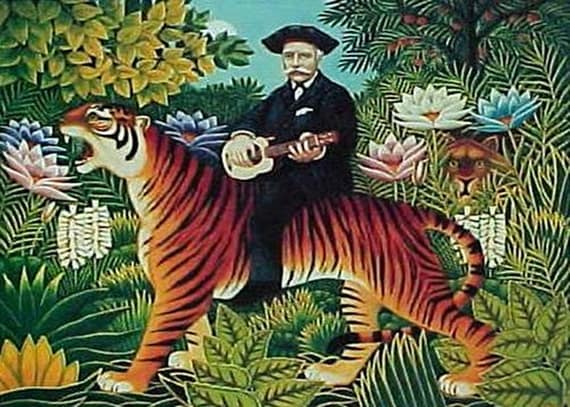

A ride on a tiger with scary consequences.

Posted by

PhilipDavid Ellwand,

Erasmus+ Projects

University of Chester

bdbo@chester.ac.uk

- in fact, as with pensions where investments haven’t fully kept pace, current contributors used to pay for most of current beneficiaries, but that’s a side issue and the relationship is changing. Historic contributions is a useful shorthand